Books Written by John W. Lundin

International ski History Association

Skade and Harold S. Hirsch Awards

Skade Awards are presented by the International Ski History Association to outstanding works on ski history. Skade is the Norse goddess associated with bowhunting, skiing, winter, and mountains. Harold S. Hirsch Awards for Excellence in Snowsports Journalism are given by the North American Sports Journalists’ Association to the best winter sports publication every three years. The Western Ski Heritage prize is awarded by the Far West Ski Association to recognize the best effort or publication in the prior 2 years that communicates the contributions of snowsports to the community at large.

John’s books are available at local bookstores (which he recommends you support), Arcadia Publishing and Amazon.

EARLY SKIING ON SNOQUALMIE PASS

Early Skiing on Snoqualmie Pass, was published by The History Press in 2017, with a foreword by Washington State Ski & Snowboard Museum (WSSSM) President Dave Moffett. The book discusses the history of skiing (Nordic and Alpine) on Snoqualmie Pass in particular, and in Washington generally, and contains 120 historic photos. The book was written as part of John’s work helping to start the Washington State Ski & Snowboard Museum that opened on Snoqualmie Pass in October 2015, to which John is donating his author’s profits.

The book describes the exciting early days of skiing when Washington was called “the Switzerland of America”; Washington and the Pacific Northwest “concededly [have] the greatest skiing in North America”; and Snoqualmie Pass was the epicenter of the sport, “where modern skiing was born and raised.”

The book traces several themes. First, how Norwegian immigrants made ski jumping the most popular winter sport in the early days of skiing. Second, the role of newspapers in promoting early skiing. Third, how railroads (Northern Pacific, Great Northern and Milwaukee Road) supported the early ski industry. Fourth, how Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Programs (CCC, WPA and Forest Service) played important roles in the development of skiing in the 1930s.

The book describes the ski jumping tournaments that attracted world-class competitors and thousands of spectators to Cle Elum, Beaver Lake on Snoqualmie Summit, Leavenworth, and the Milwaukee Ski Bowl at Hyak. A number of National Ski Jumping championships were held in Washington, distance records were set there, and the 1948 U.S. Olympic Jumping team was selected at the Ski Bowl. The Mountaineers’ twenty-mile race from Snoqualmie to Stampede Pass, “the country’s longest and hardest race,” was a pinnacle of cross-country skiing. Alpine skiing began in private ski clubs on Snoqualmie Pass, and expanded in 1934, when the Seattle Park Department opened the country’s first Municipal Ski area on Snoqualmie Pass, the Seattle Municipal Ski Park. Alpine skiing grew in popularity as a result of several events in the mid-1930s: the Silver Skis Race on Mt. Rainier (from Camp Muir to Paradise) that began in 1934, sponsored by the Seattle P.I.; the 1935 National Downhill and Slalom Championships and Olympic tryouts held on Mt. Rainier, where five Washington skiers were selected to go to Europe for the 1936 U.S. Olympic Games; the 1936 Winter Olympic Games in Germany, the where Alpine skiing first appeared; and the opening of the lavish $1.5 million Sun Valley Ski Resort in December 1936, by the Union Pacific Railroad, the country’s first destination ski area, called the American San Moritz, that transformed skiing in America.

The sport reached an early high point when the Milwaukee Railroad opened its Ski Bowl at Hyak in 1938, influenced by Union Pacific’s Sun Valley Resort. The Ski Bowl offered train access from Seattle in two hours, a modern ski lodge, an overhead cable lift (called a Sun Valley type lift without chairs), lights for night skiing, and free ski lessons for Seattle high school students provided by the Seattle Times. It was the state’s first modern ski area that revolutionized local skiing and brought thousands into the sport. The Northern Pacific Railroad considered opening a major new ski area at its Martin stop, near Stampede Pass, in the late 1930s, and operated the Martin Ski Dome, a small facility, until WW II.

Army Mountain Troops trained on Mt. Rainier from 1940 – 1942, before moving to Camp Hale, Colorado. Skiing exploded in popularity after the war, as ski areas were expanded and new ones opened to meet the demand. When the Milwaukee Ski Bowl Lodge burned down in December 1949 and the area was not reopened after the 1950 ski season, Alpine skiing in Washington was set back by at least a decade. However, ski jumping continued at Leavenworth until 1978, where national championship tournaments were held and three national distance records were set between 1965 and 1970. Alpine skiing expanded as new ski areas opened in the late 1950s and 1960s. WSSSM Board Member, lawyer and local ski historian John W. Lundin follows the sport’s historic tracks and the evolution of Washington skiing.

John was interviewed about Early Skiing on Snoqualmie Pass on Rainier Avenue Radio about “Sports and Stuff” in 2019.

Two Histories Of Idaho's Wood River Valley &

The Sun Valley Ski Resort

In 2020, John published two companion books that give an unparalleled insight into the history of the Wood River Valley and the Sun Valley resort: Sun Valley, Ketchum and the Wood River Valley, and Skiing Sun Valley: a History from Union Pacific to the Holdings. John is donating his author’s profits from both books to the Center for Regional History at The Community Library in Ketchum.

Sun Valley, Ketchum and the Wood River Valley is an Images of America series book that uses 200 classic photographs to describe the history of Idaho’s Wood River Valley, from its early days as one of the country’s silver producing capitals, to the opening of the Sun Valley Ski Resort by Union Pacific Railroad in1936. The book received a Skade honorable mention award from the International Ski History Association in 2021, as an outstanding ski history publication.

Skiing Sun Valley: a History from Union Pacific to the Holdings is an in-depth history of the Sun Valley Resort, built by Averell Harriman and the Union Pacific Railroad in the remote mountains in Idaho in 1936. Sun Valley was the country’s first destination ski resort where Union Pacific engineers invented the chairlift, and modern skiing in this country began. In 2021, the book won two prestigious national book awards: a Skade award from the International Ski History Association to honor outstanding ski history publications; and the Harold S. Hirsch Award for Excellence in Snowsports Journalism given by the North American Sports Journalists’ Association (NASJA) to the best winter sports publication every three years.

Sun Valley, Ketchum and The Wood River Valley

2021, Skade Honorable Mention

Sun Valley, Ketchum and the Wood River Valley, is an Images of America series book from Arcadia Publishing. The book uses 200 historic images to describe the history of the Wood River Valley, from its mining era that brought a Union Pacific branch line into the Valley in 1883, through sheep herding and agriculture in the late 1800s and first few decades of the 1900s. These economic eras developed and maintained the rail infrastructure necessary for the establishment of the Sun Valley Ski Resort in 1936 by Averell Harriman and the Union Pacific Railroad. When Harriman sent Count Felix Schaffgotsch to tour the west in late 1935, to find the ideal location for a new ski resort, it had to be on an existing Union Pacific rail line.

Sun Valley and Ketchum are in Idaho’s Wood River Valley, gateway to back country and wilderness areas. Settlers first arrived in the valley in the early 1880s, attracted by a silver rush. Goods were shipped in and out of the valley on wagon roads linking the area to railroad stops between 135 and 170 miles away. In late 1881, the $500,000 Philadelphia Smelter opened north of Ketchum at the mouth of the Warm Springs Canyon, to smelt the galena ore produced in the valley and surrounding mining districts. Between 1881 – 1884, Union Pacific built a new rail line from its main-line in Granger, Wyoming, through Idaho to Portland, Oregon, using a subsidiary, the Oregon Short Line (OSL). In 1882, U.P publicist Robert Strahorn convinced the railroad to build the Wood River Branch between Shoshone and Hailey, to access the valley’s rich silver industry. He and other U.P. insiders formed the Idaho and Oregon Land Development Company to obtain land and develop towns where they knew the OSL planned to have rail stops, earning significant profits. In spring 1882, his company bought the townsites of Shoshone and Hailey, knowing a branch line would built to link them, and planned to make Hailey the branch’s terminus and the valley’s economic center, “Idaho’s Denver.” In 1883, the railroad connected the valley to the outside world, brought in outside capital, and caused an economic boom. In 1884, the line was extended to the Philadelphia Smelter north of Ketchum, the railroad’s main customer, over the objections of Strahorn’s forces.

During the International Silver Depression (1888 – 1898), most of the country’s railroads went into bankruptcy, including Union Pacific and the Oregon Short Line, but the Wood River Branch was kept operating by the valley’s next industry, sheep raising and agriculture. Central Idaho benefitted greatly from the Reclamation Act of 1902, that provided federal funds to build dams and irrigation systems in the arid west. Dams were built on the Snake and Big Wood Rivers, turning vast areas of desert into productive farmland. The Oregon Short Line prospered from these new markets, and in the 1920s, Ketchum and Hill City on Camas Prairie shipped more sheep than anywhere in the world, except for sheep stations in Australia. This kept the Wood River branch in operation through the early 1930s, as the Great Depression decimated the country.

In 1936, in the middle of the Depression, Union Pacific board chairman Averell Harriman convinced the railroad to build Sun Valley, the area’s first destination ski resort, spending $2.5 million in two years ($45 million today), using its Wood River Branch for access. Sun Valley offered a lavish lifestyle, a luxurious lodge, Austrian ski instructors, and chairlifts invented by Union Pacific engineers. Known as America’s St. Moritz, it was a magnet for beautiful people and serious skiers, had a monopoly on grandeur for decades, and influenced all ski areas that developed later. Subsequent owners Bill Janss and the Holding family expanded and improved Sun Valley, making it one of the world’s premier year-around resorts. Sun Valley was rated as the country’s Number one ski resort in 2021, by Ski Magazine.

A review of Sun Valley, Ketchum and the Wood River Valley in the Mountain Express can be seen by clicking the link below:

SKIING SUN VALLEY: A HISTORY FROM UNION PACIFIC TO THE HOLDING

2021, winner of Skade and Western Ski Heritage awards, co-winner of Harold S. Hirsch prize.

Skiing Sun Valley: a History from Union Pacific to the Holdings, published by The History Press in 2020, is an in-depth history of the country’s first destination ski resort where modern skiing in this country began, that includes over 180 historic photos. The book tells previously untold stories from Union Pacific documents; oral histories of individuals involved with the resort from its beginning; histories of Union Pacific and the Harriman family; Sun Valley Ski Club reports, American Ski Annuals, and other contemporaneous materials.

Skiing Sun Valley explores Sun Valley’s relationship with Averell Harriman and the Union Pacific Railroad; Harriman’s personal involvement with virtually every decision made about the resort; and how its status was governed by railroad economics. It demonstrates how Harriman used ski tournaments to make Sun Valley an international destination; contains highlights of the resort’s major tournaments, including its Harriman Cup races; shows how back-country skiing was an important part of the resort’s attraction in its early years; and describes where and when Sun Valley’s ski lifts, lodges and runs were developed.

Averell Harriman was the son of E.H. Harriman, who led a group that bought the Union Pacific Railroad out of bankruptcy in 1897, and turned it into a major economic force and national transportation giant, making him one of the richest men in America. Averell joined the railroad’s board in 1912, while he was in college. In 1932, he became Chairman of Union Pacific’s Board with a mandate to deal with the effects of the Great Depression that caused railroad passenger service to “collapse like a rotten trestle.” In 1936, Averell convinced a skeptical railroad to build a ski resort in the remote mountains of Idaho, to recreate European ski ambiance, stimulate passenger travel, and add luster to rail travel in the winter. Sun Valley was Harriman’s pet project that was built with the “grudging acquiescence” of the railroad, according to his biographer. Showing Harriman’s power, beginning on February 20, 1936, he had the railroad buy land outside of Ketchum; hired publicist Steve Hannagan who drafted a plan for the resort, and famous architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood to design the Lodge; negotiated a contract with a Los Angeles contractor; and began construction, all before Union Pacific’s Board approved the project on May 5, 1936.

Sun Valley was a risk, since skiing in this country was in its infancy. There were few lifts so one had to be physically fit enough to hike, herringbone, or use skins to climb hills before skiing down. Equipment was rudimentary, there were few formal ski lessons, and the sport involved more back-country mountaineering than downhill skiing, limiting the sport’s appeal.

Sun Valley opened in December 1936, in the remote mountains of Idaho, built for $1.5 million by Union Pacific. Called America’s St. Moritz, it had an ultra-modern lodge and big city amenities, a ski school with Austrian instructors that made skiing sexy, and chair lifts invented by U.P. engineers based on a system to load bananas onto boats, so skiers could ride up its mountains quickly and in comfort. Chairs were installed on Proctor and Dollar Mountains, but not on Bald Mountain until 1940, because Baldy was seen as too challenging for most skiers at the time.

Steve Hannagan, Sun Valley’s brilliant publicist, established a “chic image” for the resort using celebrities, attractive women, Olympic stars and monied families. Articles about the resort appeared in magazines and newspapers throughout the country, it was featured in movies, and became a cultural icon embodying fun and affluence, while the country struggled with the effects of the Depression. Ski racer Dick Durrance said Sun Valley was “the most important influence in the development of American skiing…Its concentrated and highly successful glamorization of the sport got people to want to ski in the first place.” It had a monopoly on skiing grandeur for several decades and influenced all ski areas that developed later. According to Ski School Director Friedl Pfeifer:

It is hard to recapture the fascination Sun Valley had back then as a romantic oasis. The social whirl that centered around the Duchin Room in the Sun Valley Lodge, where an orchestra played every night, made Sun Valley a never-never land where everyone was rich and young and all invited to the dance.

Sun Valley became a grand vision of a paradise for Seattleites, which could be reached in comfort and safety on Union Pacific trains. The Seattle Times said “Sun Valley is 26 hours from Seattle by train, and 20 hours by car, but it might as well be in Seattle’s back yard” because of the number of Seattleites who went there. The Seattle Times mentioned Sun Valley 227 times in 1937, and more the next year.

Sun Valley offered young, talented skiers room and board, jobs, coaching and chairlifts for the training necessary to compete on the international circuit. British skiing authority Arnold Lunn said “to achieve the standard of a FIS or Alrberg-Kandahar winner, a skier needs weeks of practice during which he can have his 10-15,000 feet of downhill skiing in the day. A skier who has to climb every foot is lucky if he can average 4-5,000 feet a day.” At Sun Valley, a skier could get in more than 35,000 vertical feet a day using its chairlifts. Harriman Cup Tournaments were the country’s most prestigious and competitive events, attracting the world’s best skiers. The American Ski Annual 1943 said, “just as it is the dream of every tennis player to compete once at Wimbledon, it is every skier’s hope to participate in the famous Harriman Cup Races at Sun Valley.” U.S. Olympic teams trained at Sun Valley, and the 1948 and 1952 U.S. Olympic teams were selected there. Best known is Gretchen Fraser, who won a gold and silver medal at the 1948 St. Moritz Games, the first American to win an Olympic medal in skiing.

Sun Valley was never intended to make a profit, and required a significant subsidy from Union Pacific, ranging from 1/4 million to 3/4 million dollars a year. Harriman said “we didn’t run it to make money; we ran it to be a perfect place…and the publicity I thought was worth very much more than the deficit.” Harriman’s biographer said Sun Valley was the most satisfying venture of his business career, which transcended the bottom line of company profits, was his mark on the railroad and his own playground. For five years, he “fussed over Sun Valley as he had none of his other business enterprises.”

Averell Harriman began his war service in 1940, eventually serving as the Administrator of the Lend-Lease program in England and as Ambassador to the Soviet Union. After the war, he served as U.S. Ambassador to Britain and President Truman’s Secretary of Commerce, severed his ties with Union Pacific, and never again had a management role with the railroad. This was a turning point for Sun Valley, since the resort was Harriman’s pet project, never fully supported by railroad management.

Sun Valley served as Naval Rehabilitation Hospital during WWII. In fall 1945, resort manager Pat Rogers prepared a report discussing the extensive work that was necessary to bring Sun Valley back to be able to accommodate guests in its traditional style. This large capital investment, along with the annual subsidy, caused skeptical railroad executives to consider not reopening the resort. Steve Hannagan told the railroad that Sun Valley gave publicity to Union Pacific “at a cost, cheaper than any other known means.”

If we are not prepared to subsidize the endeavor, as an advertising, good will and business projecting endeavor, to the extent of $350,000 to $500,000 annually, it should be abandoned.

Sun Valley reopened in December 1946, to a changed world. The resort attracted skiers from a broader range of social and economic levels, not just the rich and famous, and focused on convention business. Increasing competition from airlines and cars caused rail passenger traffic to plunge in the 1950s, and Union Pacific reduced its subsidy, eroding the level of service.

Sun Valley still had international influence. In 1936, Sun Valley brought European ambiance to America and was called this country’s St. Moritz. In 1950, an Austrian newspaper said with the help of the Marshall Plan, its Arlberg ski resorts could become “as spectacular as Sun Valley.” Sun Valley continued to be the country’s primary destination ski resort and center of ski racing, and employed some of the world’s best skiers in its ski school.

Sun Valley author and ski racer Dick Dorworth described the area in an article, “Sun Valley’s Ski Racing Roots.”

Baldy was the finest ski mountain I’d ever seen…[T]here was nothing—nothing—to match the sight of Stein Eriksen skiing a run called Canyon…But no one has ever skied quite like Stein…Some of the other skiers we studied, emulated, idolized and made friends with included Christian Pravda, Jack Reddish and Dick Buek, all of them working as instructors or patrolmen for Sun Valley in 1953. Can anyone today even imagine Lindsey Vonn, Ted Ligety, Bode Miller, Mikaela Shiffrin or Marcel Hirscher working for Sun Valley, living in the dorms, eating in the employee cafeteria, training and racing on the side and being a normal part of the working culture of Sun Valley?

Union Pacific’s failure to invest in the resort in the 1950s caused its physical plant to decline and “elegance to go,” as the railroad focused on freight traffic. In 1964, unwilling to make additional investments in the resort, Union Pacific sold Sun Valley to the Janss Company. U.P. President Stoddard said “the operation of Sun Valley has been rather remote from our business of running a railroad.” Averell Harriman disagreed with the decision to sell the resort.

I never would have approved that sale if I had stayed on the Board…From the standpoint of the railroad financially, it might have been wise. But I thought it was very important for the goodwill of Union Pacific to keep Sun Valley, that it would always stay there…

Sun Valley has had three owners since 1936. Each showered the resort with love, support and money (at least for Union Pacific when Harriman was involved), and took it to a new level. However, each change of ownership resulted in disruptions of the life style to which locals were accustomed, causing initial ill will in the community.

Bill Janss said Union Pacific wanted out of Sun Valley so badly in 1964, “they’d been hawking it on the streets,” but that “[b]uying Sun Valley was like buying a national park.” Janss brought the resort back and created a year-around community, but lacked the financial resources to take it to the next level. In 1977, Janss sold Sun Valley to the Holding family, owners of Sinclair Oil Company, who said they saw “Sun Valley as a grande dame that has been sitting on her laurels…We want to make it a masterpiece again.” The Holdings remade Sun Valley into one of the country’s premier year-around resorts and restored its international status. However, unlike the 1930s and 1940s, when Sun Valley was the only high-end destination ski resort, it is now part of a highly competitive market with other resorts started after WWII.

Nonetheless, thanks to the Holdings’ stewardship, in 2021, Sun Valley was named the country’s Number One ski resort by Ski Magazine. “Sun Valley has a rich and storied history, but it was its most recent investments and innovations that helped land its first-ever win as top ski resort in North America,” according to a Sun Valley Resort news release.

A video of Skiing Sun Valley made for 2021 ISHA award ceremony can be seen by clicking the link below:

“There have been many attempts to tell the story of Sun Valley, but this book does so with a thoroughness and flair that this iconic resort deserves. With over 150 photographs and the benefits of extensive research, this book unfolds a history that dazzles with tales of celebrities…and icons of American skiing…Here is the storied past of a one of a kind place in a book that does its heritage justice.”

Reviews in Eye on Sun Valley:

“John Lundin’s Ski History Honored Even as He Pens New Book on Ski Jumping in Washington,” May 21, 2021.

“John Lundin Honored by International Ski History Association,” May 21, 2021.

“Skiing Sun Valley – a Virtual Look,” February 9, 2021.

“Sun Valley Resort Could Have Been a Rich Man’s Club had Averell Harriman’s Original Vision Been Realized,” December 15, 2020.

Review in Skiing History July/August 2021 “A Must Read for Sun Valley Fans,” by Dick Dorworth.

“Skiing Sun Valley is a deeply re-searched, scholarly book about the connections between the Sun Valley of today and the people, places, cultures, economics, wars, inventions, wilderness, ecology, risks, and personal relationships in the 19th and 20th centuries that made it what it will be in the 21st. Every aspect of the story is accompanied by an abundance of photos that on their own are worth the price of the book. Every person with a connection to and love for Sun Valley will be better informed, inspired and wiser after reading it.”

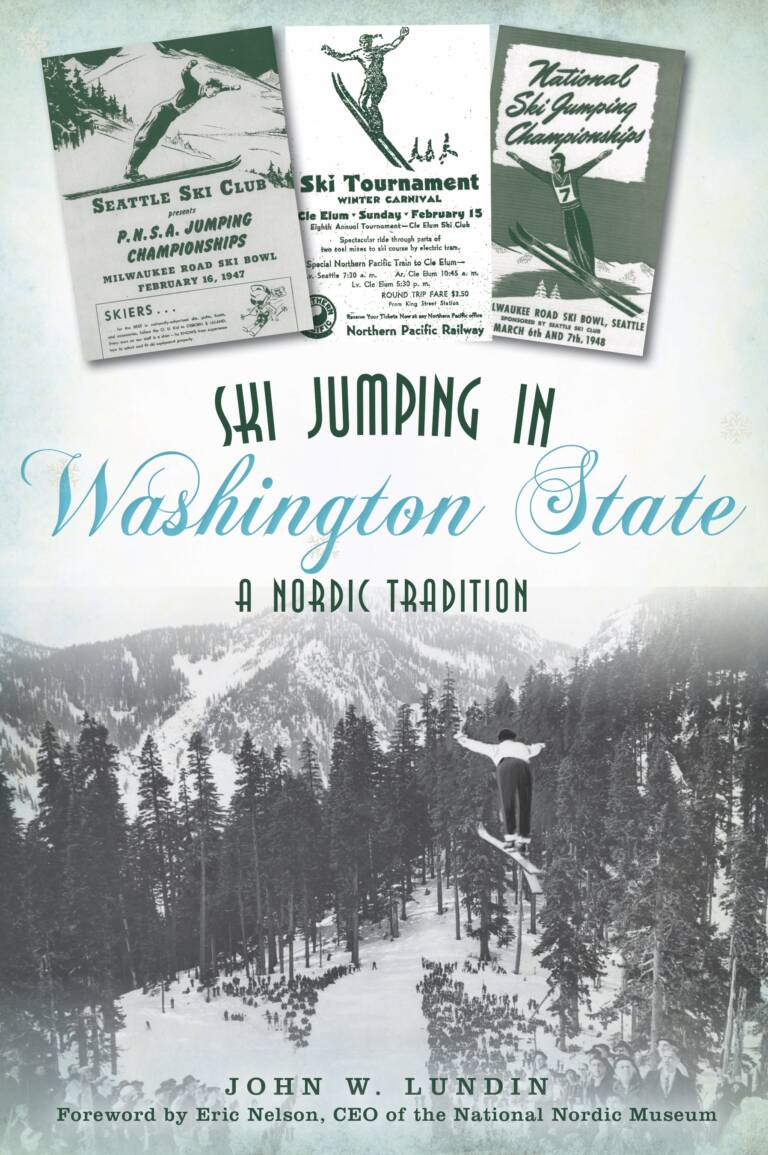

SKI JUMPING IN WASHINGTON STATE: A NORDIC TRADITION

Ski Jumping in Washington State: a Nordic Tradition was written as part of a joint exhibit in spring 2021, between the National Nordic Museum and the Washington State Ski and Snowboard Museum, that John helped to organize. Using 120 historic pictures, the book traces the history of what was Washington’s most popular winter sport, introduced by Norwegian immigrants in the early twentieth century. Eric Nelson, CEO of the National Nordic Museum in Seattle, wrote a forward for the book.

The book can be purchased from the National Nordic Museum and the Washington State Ski and Snowboard Museum: from Arcadia Publishing, Amazon and other national sources; and from local bookstores.

Ski jumping originated in Norway, where it was just a part of normal skiing, and children

learned it at a young age. Harold Anson, in his book Jumping Through Tme: A History of Ski Jumping in The United States and Southwest Canada, said “[g]etting from one farm to another in Norway in winter often involves a climb on skis up one side of a hill, and ski jumping developed as a means of clearing obstacles when skiing down the other side.” Ski Jumping was brought to this country by Norwegian immigrants, and made its way to the Northwest, according to Anson. “[W]herever two or three Norwegians gathered together, they constructed a jump and held competitions. This was never so true than in the Pacific Northwest, as a wave of new clubs showed up along the coastal mountain ranges.”

Ski jumping events in the Northwest began in British Columbia at Rossland (1898) and Revelstoke (1915). In January 1913, Olaus Jeldness (founder of the Rossland Winter Carnivals) organized a “skee” jumping and “running” exhibition at Spokane’s Brown’s Farm on Moran Prairie. In 1916, after a heavy snowfall, Seattle’s Norwegian businessmen held a jumping exhibition on Queen Anne hill, where its steepest street was made into an “ideal sliding incline.”

Between 1917 and 1924, midsummer jumping tournaments were held at Paradise Valley on Mount Rainier, “the second place in the world [after Finse, Norway] where the finest skiing may be obtained during the summer months,” according to the Seattle Times. The tournaments were “similar in every detail to that practiced in Norway,” and competitors could return to Norway “and put up the stiffest fight for honors.” The tournaments attracted the west’s best jumpers, including a “girl ski jumper,” recent Norwegian immigrant Olga Bolstad, who competed against the men and won, the delight of the press, becoming “champion of the Pacific coast on skis.”

The sport expanded statewide as new ski clubs were formed in the late 1920s. Yearly tournaments took place at ski jumps constructed by the Cle Elum Ski Club (“one of the most hazardous in the world, 6% steeper than any in Norway”); Seattle Ski Club at Beaver Lake on Snoqualmie Pass (“more tremendous length and pitch than any other hill…so steep that none but the best will attempt it”); Leavenworth Winter Sports Club (“one of the best in North America”); and Cascade Ski Club at Mt. Hood, Oregon. Events were also held at Mt. Baker, Spokane, Bend, Oregon, and elsewhere. In 1939, a world-class jumping hill was built at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl at Hyak (“the biggest and best in the U.S.”), where major national tournaments were held, including the 1940 National Four-Way Championships, National Ski Jumping Championships in 1941 and 1949, and the final tryouts for the U.S. Olympic Jumping team for the 1948 St. Moritz Games.

Tough Norwegians drove on icy roads to the tournaments to compete for the glory of the sport, since there were no monetary prizes. Competitors often had to hike long distances to reach the jumps (one + miles at Mt. Rainier; two miles at Cle Elum; and 3/4 of a mile at Snoqualmie Pass, not a hike “to encourage attendance,”), carrying heavy wooden skis. At the jumping sites, competitors had to climb steep scaffolds or hills to reach the take-off points before soaring long distances off the jumps, repeating the process multiple times. Tournaments attracted many thousands of hardy spectators, mainly Scandinavians, who traveled by car or train, hiked long distances up steep hills through the snow to reach the jumping sites, and stood outdoors for hours, often in snow-storms. In December 1937, Olav Ulland from Kongsberg, Norway, (the first person to break the 100-meter mark), came to Seattle to teach ski jumping, and became a mainstay of local skiing.

The intense battle for jumping supremacy and to set new national distance records received extensive press coverage and captured the country’s imagination. Top ski jumpers were celebrities, much like professional quarterbacks are today. Washington tournaments attracted the world’s best ski jumpers, including Birger and Sigmund Ruud, Reidar Andersen, Olav and Sigurd Ulland, Alf Engen, Torger Tokle, U.S. Olympic Jumping teams, and many others.

At the 1939 Leavenworth tournament, Sigurd Ulland (1938 National Champion) soared 249 feet, setting a new American distance record. However, the same day, Sun Valley’s Alf Engen jumped 251 feet at Big Pines, California. Later, Bob Roecker jumped 257 feet at Iron Mountain, Michigan. In 1940, Engen beat emerging jumping star Torger Tokle in the jumping portion of the National 4-Way Championships at Washington’s Milwaukee Ski Bowl, and become the National 4-Way Champion.

In 1941, at Iron Mountain, Alf Engen jumped 267 feet to set a new national distance record. Two hours later at Leavenworth, Torger Tokle jumped 273 feet – the Seattle Times said “too bad Alf!” Three weeks later, Tokle jumped 288 feet during the 1941 National Jumping Championships at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl, replacing Alf Engen as National Champion. In 1942, Tokle set another new distance record at Iron Mountain, of 289 feet.

After WWII, the future of ski jumping in the Northwest was in jeopardy, as the original Norwegian immigrants were getting older, dropping out of competition, or entering the senior class. Beginning in 1947, ski jumping was saved by an influx of Norwegian exchange students who studied at Northwest schools, who rejuvenated the sport, led by Gustav Raaum (the junior Holmenkollen champion).

The Milwaukee Ski Bowl closed in 1950, after its lodge burned down, and Leavenworth became the epicenter of Washington ski jumping. In 1950, Hermod Bakke redesigned its hill to conform to new National Ski Association standards, making it “one of the best in North America,” able to host F.I.S sanctioned competitions. In 1956, Leavenworth’s Class A trestle was rebuilt to new national standards, after a snowfall caused it to collapse, enabling the club to host national championships in 1959, 1967, 1974 and 1978, and several qualifying competitions for U.S. Olympic teams. Between 1965 and 1970, three new North American distance records were set on the Leavenworth hill.

Interest in ski jumping in North America began to flag in the 1960s, and fell off significantly in the 1970s. Areas with long jumping traditions stopped hosting tournaments: Multopor Hill on Mount Hood in 1971; Revelstoke, B.C. in 1974; and the Kongsberger Ski Club in 1974. In 1978, Leavenworth, “lacking the funds to be re-contoured to meet the revised USSA requirements, shut down after hosting the US Nationals..,” according to Anson.

Ski jumping developed as an expression of Norwegian cultural pride – a competitive sport and a way to socialize and connect immigrants to their adopted land. Ski jumping events were common occurrences on winter weekends during the early to mid-1900s, but the sport and its cultural ties are now largely forgotten in America. Ski Jumping in Washington State: a Nordic Tradition, recreates the sport’s glory days.

Ski Jumping in Washington State: a Nordic Tradition, is the companion book to an exhibit John helped organize, Sublime Sights: Ski Jumping and Nordic America, sponsored by the National Nordic Museum and the Washington State Ski and Snowboard Museum, that ran at Seattle’s National Nordic Museum from April 17 to July 18, 2021.

John Lundin’s Ski History Honored Even as He Pens New Book on Ski Jumping in Washington,” “Eye on Sun Valley, May 21, 2021”.

John gave the exhibit’s opening lecture on April 24, 2021.

John also hosted a discussion of ski jumping with Washington’s two living Olympic ski jumpers.